Population Increases That Resulted From the Baby Boom of the 1950s and 1960s Contributed to a

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Demography." National Research Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/5355.

×

4

The Growing American Indian Population, 1960–1990: Beyond Census

Jeffrey Due south. Passel

Introduction

For decades through 1960, the American Indianane population, as enumerated in U.S. censuses, grew little if at all. From a population of 248,000 in 1890, American Indiansii increased to 524,000 in 1960. While this does represent a doubling of the population, the average annual growth charge per unit over the unabridged 70-year period was just ane.1 pct—a very low effigy resulting from high fertility and very high mortality. Since 1960, the Native Americanthree population has exhibited explosive growth, increasing from 552,000 to 1,959,000, or 255 pct. The average annual growth rate of four.3 percent, extending over a 30-year catamenia, is demographically impossible without immigration. Previous research (Passel, 1976; Passel and Berman, 1986) has shown that this boggling growth was accomplished through changing patterns of racial cocky-identification on the part of people with only partial or distant American Indian ancestry, coupled with relatively high fertility and improving mortality.

| i | In general, the terms "American Indian" and "Native American" are used interchangeably here to refer to the combined census categories of American Indian, Eskimo, and Aleut. Any use of other definitions is noted in the text. |

| two | The census figures cited in this judgement for 1890 and 1960 refer only to American Indians; Alaska Natives are not included. |

| 3 | Including American Indians, Eskimo, and Aleuts. |

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Demography." National Research Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Irresolute Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

Data Collection Methods

Data on the American Indian population nerveless in the 1970, 1980, and 1990 censuses are based on cocky-identification. That is, persons answering the census choose their response to the race question. A person choosing the American Indian racial response did non have to provide whatever substantiation or documentation of this identification. At that place was no requirement that an "American Indian" be enrolled equally a member of a recognized tribe or that any tribal group recognize the respondent as a member, and there was no "blood quantum" requirement. This method of identification differs from that of previous censuses, in which a person's racial identification tended to be assigned by an enumerator, usually based on observation, local knowledge, or custom. Thus before 1970, a person would be classified equally American Indian if he or she ''looked" Indian, was recognized past the local community as American Indian, or lived in an American Indian area.

Collection of racial data based on self-identification aids overall demography taking by permitting respondents to fill out their ain census forms, thus reducing the need for expensive in-person interviews. At the same fourth dimension, self-identification adds a temporal component to the data. The responses elicited from the aforementioned individual (or grouping of individuals) may change over time in response to social, political, or economic atmospheric condition or variations in question diction. New identities may emerge, or old ones may disappear. Even though the names of groups or categories often remain the same from census to census, each census actually represents a "snapshot" in time, capturing the content of the moment, especially when data are based on self-identification. Analysts and other information users must be aware of underlying response patterns to interpret changes correctly.

For the American Indian population, the changes in method of identification between the pre-1960 and mail-1960 periodsiv have been associated with substantial changes in the nature of the information. In add-on, the American Indian population has undergone rapid demographic modify, including sizeable population growth coupled with substantial geographic redistribution. Many of these decadal changes have already been documented—Passel (1976) for the 1960–1970 decade; Passel and Berman

| iv | The 1960 census represented a transition from the enumerator-conducted censuses through 1950 and the near entirely mail service censuses since 1970. The 1960 demography was actually a hybrid of data collection methodologies, with well-nigh census forms being mailed to respondents, only all forms existence nerveless in person past enumerators. The 1960 data themselves also appear to be transitional between enumerator identification and cocky-identification. |

Suggested Commendation:"iv The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Census." National Research Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Census and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

(1986) and Snipp (1989) for 1970–1980; and Passel (1992), Eschbach (1993), and Harris (1994) for 1980–1990.

Overview of the Chapter

This affiliate expands on previous piece of work by using various demographic measures to illustrate the magnitude of changing self-identification among the American Indian population and draws some implications for data assay. Information technology provides some basic demographic background on the size, growth, and geographic structure of the American Indian population, while explaining some of the factors contributing to the boggling increase in this population. Specifically, the next section focuses on differentiating the growth nationally according to demographic versus nondemographic factors. For example, the 1990 census count of 1,959,000 American Indians exceeds by 10 percent or 189,000 the figure expected on the basis of the 1980 census and demographic components of change (i.e., births and deaths) during the 1980s. This relatively large "excess" count comes on top of a 26 percent "excess" in the 1980 census count (Passel and Berman, 1986). Put another manner, of the 1.4 million growth in the American Indian population between 1960 and 1990, well-nigh 762,000 is attributable to natural increase (i.east., births minus deaths) and 645,000 to nondemographic factors.

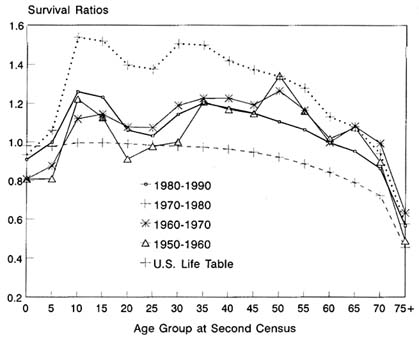

The section that follows explores some of the sources of both the demographic and nondemographic dimensions of the increase in the 1980s and earlier. Specifically, we use data on cocky-reported ancestry to demonstrate how such large increases could have occurred and what potential in that location might exist for further increases in the futurity. Nosotros and so employ various demographic measures to pinpoint changes in the age structure of the American Indian population. Demography survival ratios for this population over the last three decades evidence conspicuously that large increases are occurring for all age groups to a higher place age 10, with very notable concentrations at ages x-nineteen and to a higher place age xxx. In spite of the basic demographic constraint that age cohorts should subtract in size over fourth dimension as people die, the American Indian cohorts anile 10 to 59 in 1990 were all larger in 1990 than in 1980.

The next section uses additional demographic methods to demonstrate how the dramatic growth in the American Indian population is distributed unevenly across states. The analysis shows conspicuously that, with the exception of Oklahoma, most of the population increase attributable to changing self-identification has occurred in states that have not historically been major centers of the American Indian population. With small-scale exceptions, this design has persisted over the last 3 decades.

Suggested Citation:"four The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Council. 1996. Irresolute Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

The paper closes with a discussion of the implications of response patterns for data analysis pertaining to American Indians.

National Demographic Factors

Population Size and Growth Rate

For iii decades, from 1890 through 1920, the American Indian population hovered around 250,000, changing little from census to census (see Table 4-1). In 1930, the population jumped to roughly 330,000, where it remained for another two decades. Since 1950, the American Indian population has shown a steady upward trend, with huge numerical increases since 1970, culminating in a 1990 demography count of 1,959,000.

Average annual growth rates track these trends. From the 1890–1900 decade through 1940–1950, only the decade of the 1920s (3.ane percent) showed average annual growth exceeding 1.one per centum. In fact, for the 1890s and 1910s, the growth rates were negative as the enumerated American Indian population decreased. In 1950, growth rates began to jump

TABLE iv-one American Indian Population: 1890-1990 Censuses

| Decadal Change | |||

| Census Year | Population | Amount | Average Annual Rate |

| American Indian, Eskimo, Aleut (50 states and D.C.) | |||

| 1990 | 1,959,200 | 538,800 | 3.27 |

| 1980 | 1,420,400 | 593,100 | 5.55 |

| 1970 | 827,300 | 275,600 | 4.13 |

| 1960 | 551,700 | 208,300 | 4.01 a |

| American Indian Just (48 states and D.C.) | |||

| 1960 | 508,700 | 165,300 | 4.01 |

| 1950 | 343,400 | 9,400 | 0.28 |

| 1940 | 334,000 | 1,600 | 0.05 |

| 1930 | 332,400 | 88,000 | 3.12 |

| 1920 | 244,400 | -21,200 | -0.83 |

| 1910 | 265,700 | 28,500 | ane.xiv |

| 1900 | 237,200 | -11,100 | -0.45 |

| 1890 | 248,300 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Note: Populations rounded to hundreds. a Rate gear up equal to 48 country rate. n.a., not applicable. | |||

Suggested Citation:"four The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Enquiry Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Irresolute Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

substantially—to 4 percentage for the 1950s and 1960s and reaching a measured annual rate of 5.6 percent in the 1970s, before dropping to 3.three pct in the 1980s. Such rates are extremely high, and the 5.6 percent charge per unit for the 1970s is demographically incommunicable without international migration—a situation that characterizes the American Indian population, every bit shown below.

Error of Closure

Nosotros can gain some insight into the nature of these contempo increases in the American Indian population with some simple analytic tools of census. For a population non experiencing immigration, demographic increases come only from births and decreases only from deaths. We can express this relationship with the demographic "balancing equation," which relates the size of the population at one point in time to its size in the past:

![]()

where Pi = the population at time 1 (due east.g., 1990)

P0 = the population at fourth dimension 0 (e.1000., 1960)

B = births during the time interval (east.thou., 1960–1990)

D = deaths during the time interval

e = mistake of closure.

The final term in the equation, e or error of closure, is the corporeality needed to make the equation residue. Error of closure is usually small and unremarkably represents changes in census coverage, unmeasured demographic change (such equally immigration), or shifts in the makeup of the population. Every bit we volition come across, errors of closure since 1960 have been large for the American Indian population. They appear to have resulted from increases in the population caused by changes in cocky-identification, that is, individuals who previously did not choose to call themselves American Indian, simply did so in more than contempo censuses.

Table 4-2 shows the growth of the American Indian population and errors of closure for the last 4 decades (1950–1960 through 1980–1990). For the 1950–1960 decade, the error of closure amounts to only i,900, or 0.4 pct of the 1960 American Indian population. This error is negligible and can hands exist attributed to inaccuracies in measuring whatever of the iv components in the balancing equation. For the 1960–1970 decade, however, the error of closure is very large, amounting to 91,000, or xi percent of the 1970 population. In earlier work, Passel (1976) proved that the

Suggested Commendation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Demography." National Enquiry Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Irresolute Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

TABLE 4-2 Components of Modify and Error of Closure for American Indians: 1950–1990 Censuses

| Intercensal Period | |||||

| Component or Population | 30-Year Period 1960-1990 | 1980-1990 | 1970-1980 | 1960-1970 | 1950-1960 a |

| Final census | i,959,200 | 1,959,200 | 1,420,400 | 827,300 | 508,700 |

| Mistake of closure | |||||

| Amount | 645,400 | 188,700 | 365,500 | 91,200 | one,900 |

| Percent b | 32.9 | 9.6 | 25.7 | eleven.0 | 0.iv |

| Estimated population at final census | 1,313,900 | 1,770,600 | one,054,900 | 736,100 | 506,900 |

| Component for menses | |||||

| Natural increase | 762,200 | 350,200 | 227,600 | 184,400 | 163,500 |

| Births | 948,700 | 422,200 | 290,700 | 235,800 | 207,000 |

| Deaths | 186,500 | 72,100 | 63,100 | 51,300 | 43,500 |

| Initial census | 551,700 | ane,420,400 | 827,300 | 551,700 | 343,400 |

| Average annual charge per unit of natural increment c | 27.two | 21.ix | 24.two | 28.6 | 38.5 |

| Births | 33.9 | 26.5 | thirty.9 | 36.6 | 48.7 |

| Deaths | half-dozen.seven | 4.5 | 6.vii | 8.0 | 10.ii |

| a American Indian only. b Base of operations of percent is final census. c Per 1,000 mid-menses population, as estimated. | |||||

Suggested Citation:"iv The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Demography." National Enquiry Council. 1996. Irresolute Numbers, Irresolute Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

error of closure could not be attributed to errors in measuring the population (i.e., changes in census coverage), clearing, births, or deaths, but could be explained only by the creation of "new Indians," that is, individuals who had not previously identified as American Indian but chose to do so in the 1970 census.

For the 1980 demography, the error of closure was unprecedented, amounting to 366,000, or 26 percent of the 1980 census count. This increment, too, tin exist attributed only to irresolute self-identification (Passel and Berman, 1986). The 1970–1980 increase is particularly noteworthy in that it occurred after the large 1960–1970 increase. Thus, not but did new individuals cull to identify as American Indian, but the previous shifts were maintained.

With the 1990 census, not but were these historical shifts farther consolidated, but the tendency toward shifting identity continued. The 1990 demography count of 1,959,000 resulted in an mistake of closure for the decade of the 1980s of 189,000, or almost 10 percent. Given that the 1980s were marked past unprecedented levels of clearing (Fix and Passel, 1994), some of the mistake of coverage in 1990 has been attributed to the immigration of American Indians from Canada, Latin America, or the Caribbean (east.g., Harris, 1994). However, the foreign-born American Indian population increased but slightly between the 1980 and 1990 censuses—from 41,700 to 48,700,—while the percentage foreign-born decreased—from two.vii to ii.4 pct. Although the error of closure is not equally large, numerically or in percentage terms, equally those of the previous decades, the continued, considerable shift in identity in 1990 once again shows the enduring nature of the change.

Combining the data for the 1960–1990 period shows the magnitude of the shifts that have occurred. Between 1960 and 1990, the American Indian population increased past one,407,000, from 552,000 to 1,959,000. During these three decades, the measured natural increase of the American Indian population (i.e., the excess of births over deaths) amounted to 762,000 (see Table 4-two). This leaves almost 645,000 persons, or 33 percent of the 1990 census count of American Indians, that cannot be accounted for past demographic factors, but must exist explained past the changing nature of American Indian cocky-identification during the thirty years.

Sources Of Nondemographic Increase

The 1980 and 1990 censuses provide some information that point to the source of the shifts in American Indian cocky-identification. In addition, some elementary demographic measures tin can be used to demonstrate which historic period groups take been driving these changes.

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Demography." National Inquiry Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

Ancestry and Race

The data discussed in a higher place are from decennial census questions defining the "race" of the population; more than specifically, the information for 1980 and 1990 represent individuals choosing American Indian in response to the census question on racial identification. This question required respondents to pick among specified categories and immune just one response in both the 1980 and 1990 censuses. Nevertheless, both censuses also asked a broader question on "beginnings." The 1990 census question—worded "What is this person'southward ancestry or ethnic origin?"—required respondents to write in their own response and permitted more than one ethnic identification. These "beginnings" information are thought to elicit a broader indigenous identification, including some with lesser degrees of attachment than the racial classification (Waters, 1990).

The ancestry information bear witness a very large population that claims some degree of Indian ancestry—a much larger population than that choosing to identify with the American Indian in racial terms. In 1980, 6.eight million persons claimed American Indian ancestry, of which simply 21 percent, or 1.4 million persons, chose to identify with the American Indian racial group (Table iv-3). Likewise, in 1990, simply 22 percentage of the 8.8 million people challenge American Indian beginnings identified as American Indian past race. Thus, there is very large pool of "potential" American Indians, i.eastward., persons with some American Indian beginnings who may or may not choose to place every bit American Indian past race. In this context, the errors of closure in 1980 and 1990 correspond very minor fractions of the "potential" American Indian population—five pct in 1980 and only two percent in 1990. Thus, the possibility exists for further large increases in the American Indian population in the future, if social, political, economic,

Tabular array 4-3 American Indian Population by Race and Ancestry: 1990 and 1980 Censuses

| 1990 Census | 1980 Census | |||

| American Indian Definition | Corporeality | Per centum | Amount | Pct |

| By ancestry, total | viii,798,000 | 100 | six,766,000 | 100 |

| By race | ||||

| Census count | 1,959,000 | 22 | 1,420,000 | 21 |

| Estimate from previous census | 1,771,000 | 20 | 1,055,000 | 16 |

| Error of closure | 189,000 | 2 | 366,000 | v |

| Past ancestry, merely not past race | 6,839,000 | 78 | v,346,000 | 79 |

Suggested Citation:"four The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Quango. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

and methodological factors continue to encourage the shifts in identification.

Age Patterns of Increase

Another demographic measure, the census survival ratio (CSR), offers a tool for ascertaining whether the big increases in the American Indian population over the last four decades are concentrated in specific age groups or cohorts. The CSR is a simple measure: it is the ratio of the population in a given age cohort in one census to the aforementioned group of people in the previous census, i.e., the age group 10 years younger in the census x years earlier:

![]()

where CSRten,t = demography survival ratio for historic period × at fourth dimension t (e.thousand., ages 10–xiv in 1990)

Px,t = population aged × at time t (due east.g., aged 10–14 in 1990)

Px - x,t - 10 = population historic period × - 10 at time t - 10 (e.one thousand., aged 0–4 in 1980).

Since the American Indian population experiences negligible immigration, the CSRs should all be less than 1.0 because the population in an age cohort can only decrease through mortality. If CSRs are greater than 1.0, they bespeak move into a cohort, in the instance of American Indians through shifts in self-identification. The greater the CSR, the larger the shift into the population.

For the 1980 and 1990 censuses, the American Indian CSRs prove a very stiff age pattern of increases. For ages 10–nineteen, the CSRs exceed 1.2, indicating increases of more than 20 percent in these cohorts as they aged from 0–nine in 1980 to 10–xix in 1990. In improver, all cohorts anile xxx–59 accept large CSRs, indicating sizeable increases at these ages. Thus, the figures for ages nether 10 and 20–29 are consistent with data from the previous 10-year period, merely other cohorts show increases that can be attributable only to "new" individuals identifying equally American Indian. A virtually identical pattern shows up for the 1950–1960 and 1960–1970 decades (Figure iv-one). For 1970–1980, all of the CSRs are much higher than in other decades because the overall error of closure was much greater. For ages x–49 in 1980, the CSRs exceed ane.40, indicating at least twoscore percentage increases in size across demographic changes.

Accompanying the large CSRs are, of form, numerical increases in cohort size that have occurred for all ages ten–59 in every demography since 1960, with the exception of ages 20–34 in 1950. Particularly large increases

Suggested Citation:"four The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Enquiry Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Census and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

FIGURE 4-1 Census survival ratios for American Indians, 1950–1990.

occurred in the concluding two censuses for cohorts anile 10–49. Some bodily numbers illustrate the striking character of these changes. For American Indians built-in in the 1940s, about 96,000 were enumerated in their kickoff census, in 1950. By the fourth dimension this group had reached their 40s in the 1990 census, they had more than doubled to 223,000. Those born in the 1950s showed an even greater increment in size, from 175,000 in 1960 (at ages 0–9) to 321,000 in 1990 (at ages xxx–39). All nascence cohorts of American Indians reaching adulthood in the post-Globe War Ii era take participated in the accretions from changing self-identification.

Birth Statistics

The exceptions to demography survival ratios greater than 1.0 are the cohorts built-in in the decade earlier the census, i.e., at ages 0–9. Low CSRs are to be expected at these ages considering young children are omitted from censuses at high rates, particularly in populations such equally American Indians with large households, high poverty rates, and many difficult-to-enumerate situations (Robinson et al., 1992). Even for the 1970–1980 decade,

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Irresolute Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

with its huge increases in self-identification, the CSRs for ages under x guess the combined effects of undercoverage and mortality, implying that the shifts in identification may not occur for young children. However, for American Indians, another definitional complication arises in these early on historic period groups.

In computing CSRs for ages under x, births in the decade preceding the census are compared with the demography counts for ages 0–9. The nascence statistics are not collected in the census, but are compiled from registration data by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The organisation used by NCHS to assign births to racial groups differs considerably from that used in collecting census data. For every nascence, NCHS collects information on the race of the mother and the race of the begetter, based on self-identification.v Until 1989, births were assigned to race groups by a rule that tended to favor assignment to racial minorities. Specifically, if simply one parent was white, the child was assigned the race of the nonwhite parent; otherwise, the child was assigned the race of the father (if known). Outset in 1989, NCHS dropped its "old rule" for official classification of births by race in favor of tabulations based merely on the race of the female parent or the race of the father.

Every bit Table iv-4 shows, the "old" NCHS classification scheme produced numbers of American Indian births that are 20 percent or then higher than those produced by either the "male parent" or "mother" nomenclature. Nonetheless, none of the iii classification methods is consistent with the way children were identified in the censuses of 1980 and 1990. In their first demography, the total number of young American Indian children (under age 10) was roughly comparable to the almost inclusive classification method, i.e., the "former" NCHS rule. Nevertheless, past the time the 1970s birth cohorts had reached their teens in 1990, even this crude comparability had disappeared as the 1990 census counts greatly exceeded the numbers of births. Thus, registration information on births of American Indians from NCHS cannot exist considered comparable with decennial census figures and must clearly be used with caution. Further analyses presented beneath extend these cautions.

Geographic Distribution

The American Indian population is not uniformly distributed beyond the land; growth also has occurred differentially beyond states. American Indians are full-bodied in the western region, which had 934,000 American Indians in 1990 (Table 4-five), or 48 percent of the U.Due south. total. The

| 5 | In some cases, the information is based on observation by hospital personnel. |

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Inquiry Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Census and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

Tabular array 4-4 American Indian Births Based on Alternative Nomenclature Procedures: 1968–1989

| Race Consignment Rule | Percent Difference from Old NCHS Rule | ||||

| Year or Period | Old NCHS Rule | Female parent Rule | Father Rule | Mother Rule | Begetter Rule |

| Annual data | |||||

| 1989 | 49,267 | 39,478 | 38,667 | -19.9 | -21.5 |

| 1988 | 45,804 | 37,020 | 36,032 | -19.2 | -21.3 |

| 1987 | 43,595 | 35,222 | 34,379 | -19.2 | -21.one |

| 1986 | 42,561 | 34,087 | 33,233 | -xix.9 | -21.9 |

| 1985 | 42,521 | 33,936 | 33,338 | -20.2 | -21.6 |

| 1984 | 41,160 | 33,081 | 32,145 | -xix.6 | -21.nine |

| 1983 | 41,269 | 32,774 | 32,518 | -twenty.six | -21.2 |

| 1982 | forty,901 | 32,288 | 32,147 | -21.ane | -21.four |

| 1981 | 37,000 | 29,517 | 29,594 | -xx.2 | -20.0 |

| 1980 | 36,618 | 29,212 | 29,517 | -20.2 | -19.4 |

| 1979 | 34,021 | 27,305 | 27,567 | -xix.7 | -19.0 |

| 1978 | 32,955 | 26,497 | 26,919 | -19.6 | -18.3 |

| 1977 | thirty,460 | 24,764 | 25,172 | -18.vii | -17.4 |

| 1976 | 28,966 | 23,768 | 24,100 | -17.ix | -16.viii |

| 1975 | 27,531 | 22,684 | 23,048 | -17.6 | -xvi.3 |

| 1974 | 26,600 | 22,169 | 22,330 | -xvi.7 | -16.1 |

| 1973 | 26,420 | 22,255 | 22,084 | -15.8 | -16.4 |

| 1972 | 27,314 | 23,301 | 22,977 | -14.7 | -15.9 |

| 1971 | 27,110 | 23,222 | 22,754 | -fourteen.three | -16.1 |

| 1970 | 25,838 | 22,242 | 21,940 | -thirteen.9 | -15.i |

| 1969 | 23,938 | twenty,830 | 20,670 | -13.0 | -13.7 |

| 1968 | 24,250 | 21,484 | 20,380 | -11.4 | -16.0 |

| Five-Year Periods | |||||

| 1985–1989 | 223,748 | 179,743 | 175,649 | -19.7 | -21.v |

| 1980–1984 | 196,948 | 156,872 | 155,921 | -20.3 | -twenty.eight |

| 1975–1979 | 153,933 | 125,018 | 126,806 | -eighteen.eight | -17.6 |

| 1970–1974 | 133,282 | 113,189 | 112,085 | -xv.one | -15.9 |

| 1970–1989 | 707,911 | 574,822 | 570,461 | -xviii.8 | -19.4 |

| NOTES: Numbers rounded to hundreds; percents based on unrounded numbers. Alternative race consignment rules: Old NCHS Rule—Race of birth is assigned to nonwhite parent in white/nonwhite couple; assigned Hawaiian if either parent is Hawaiian; otherwise, assigned race of father, if known. Mother Rule—Race of nascence is assigned to mother'due south race. Father Dominion—Race of birth is assigned to father's race, if known. SOURCE: Unpublished tabulations from the National Heart for Wellness Statistics. | |||||

Suggested Commendation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Census." National Inquiry Quango. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Census and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/5355.

×

southward had the next largest number with 563,000, or 29 percent. Just a scattering of states have large American Indian populations. Only iv had more than 100,000 in 1990: Oklahoma (252,000), California (242,000), Arizona (204,000), and New Mexico (134,355). There were another nine states with 45,000–100,000 American Indians: Alaska (86,000), Washington 81,000), North Carolina (80,000), Texas (66,000), New York (63,000), Michigan (56,000), Southward Dakota (51,000), Minnesota (50,000), and Montana (48,000). These top 13 states had 72 pct of the 1990 total U.S. population of American Indians.

The one,959,000 American Indians represent merely 0.viii pct of the 1990 total U.S. population. In every country, the American Indian population constituted simply a small minority of the population, with Alaska having the largest percentage at 15.6 per centum. In only seven other states did American Indians stand for as much equally 2 percent of the total population: New United mexican states (8.9 percent), Oklahoma (8.0), South Dakota (7.three), Montana (6.0), Arizona (5.six), North Dakota (four.1), and Wyoming (two.1).

Errors of Closure for States

The geographic concentration of American Indians has actually decreased substantially over the last 40 years. In the 1950 demography, nineteen states plus Alaska had 3,000 or more than American Indians and accounted for 93 pct of the full U.S. American Indian population. These states have represented a steadily decreasing percentage of the American Indian population since then: 90 percent in 1960, 84 in 1970, 81 in 1980, and only 78 per centum in 1990. This deconcentration has occurred in function because of migration from the original xix states to the other 31 (Eschbach, 1993). However, most of the deconcentration is actually owing to changes in self-identification because increased reporting equally American Indian, every bit measured by error of closure, has occurred disproportionately in u.s. that did not have large American Indian populations in 1950.

We outset divide u.s.a. into 2 groups: nineteen states that historically have had large American Indian populations, i.due east., more than 3,000 American Indians in 1950, and are designated ''Historical Indian" states6 or simply "Indian states;" and the remaining 31 states plus the District of Columbia, which historically have not had large American Indian populations

| vi | The xix states are New York, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, New United mexican states, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Washington, Oregon, and Alaska. California had more than three,000 American Indians in 1950, simply is excluded from the "Indian" states because information technology had very few organized tribes and a very different blueprint of population alter from that of the other 19 states over the 1950–1980 menstruum. |

Suggested Commendation:"four The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Enquiry Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Wellness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

TABLE 4-five American Indian Population and Components of Alter, for Regions, Divisions, and States: 1980–1990

| Census Counts | Average Almanac Rate a | Estimated 1990 Population | Error of Closure (Implied Migration) | ||||||

| Region, Sectionalization and Country | 1990 | 1980 | Births 1980–1990 | Deaths 1980–1990 | Nascence | Expiry | Corporeality | Per centum b | |

| U.South., Total | 1,959,200 | ane,420,400 | 422,200 | 72,100 | 25.0 | four.3 | 1,770,600 | 188,700 | 9.6 |

| Indian States* | one,287,500 | 951,100 | 317,600 | lx,000 | 28.4 | five.four | one,208,700 | 78,700 | 6.1 |

| Non-Indian States | 671,800 | 469,300 | 104,600 | 12,100 | 18.iii | 2.i | 561,800 | 110,000 | 16.four |

| Northeast | 125,100 | 79,000 | 15,600 | two,900 | 15.2 | ii.nine | 91,700 | 33,500 | 26.eight |

| Midwest | 337,900 | 248,400 | 75,400 | xiii,800 | 25.7 | iv.7 | 310,000 | 27,900 | eight.3 |

| South | 562,700 | 372,200 | 90,100 | xvi,300 | 19.3 | 3.5 | 446,000 | 116,700 | 20.7 |

| West | 933,500 | 720,700 | 241,200 | 39,000 | 29.ii | 4.7 | 922,900 | 10,600 | 1.ane |

| New England | 32,800 | 21,600 | 5,000 | 800 | 18.two | 3.0 | 25,700 | seven,100 | 21.5 |

| Maine | 6,000 | 4,100 | 1,200 | 200 | 23.8 | 4.3 | 5,100 | 900 | 15.4 |

| New Hampshire | two,100 | 1,400 | 200 | 0 | 11.eight | 1.three | 1,500 | 600 | 28.one |

| Vermont | 1,700 | 1,000 | 100 | 0 | 7.0 | 0.v | one,100 | 600 | 36.9 |

| Massachusetts | 12,200 | 7,700 | one,900 | 200 | nineteen.4 | 2.3 | 9,500 | ii,800 | 22.seven |

| Rhode Island | four,100 | 2,900 | 800 | 200 | 24.two | 6.1 | 3,500 | 500 | 13.three |

| Connecticut | 6,700 | 4,500 | 700 | 100 | 12.1 | 2.4 | v,100 | 1,600 | 23.vii |

| Heart Atlantic | 92,400 | 57,400 | 10,600 | 2,100 | 14.2 | 2.8 | 65,900 | 26,400 | 28.6 |

| New York* | 62,700 | 39,600 | seven,000 | ane,600 | 13.7 | iii.1 | 45,000 | 17,600 | 28.1 |

| New Jersey | 15,000 | 8,400 | ii,100 | 300 | 17.viii | two.nine | 10,100 | 4,800 | 32.ii |

| Pennsylvania | 14,700 | 9,500 | 1,500 | 200 | 12.4 | 1.7 | x,800 | four,000 | 27.0 |

| East N Central | 149,900 | 105,900 | 24,100 | iv,300 | 18.viii | 3.4 | 125,700 | 24,300 | 16.2 |

| Ohio | 20,400 | 12,200 | 3,100 | 400 | eighteen.nine | two.five | 14,900 | v,500 | 26.8 |

| Indiana | 12,700 | seven,800 | 1,100 | 100 | 10.8 | 0.6 | 8,900 | 3,800 | xxx.ii |

| Illinois | 21,800 | xvi,300 | 3,300 | 500 | 17.i | 2.7 | 19,000 | 2,800 | 12.9 |

| Michigan* | 55,600 | xl,100 | 7,500 | 1,400 | fifteen.7 | 2.9 | 46,200 | 9,500 | 17.0 |

| Wisconsin* | 39,400 | 29,500 | nine,200 | 2,000 | 26.six | v.7 | 36,700 | ii,700 | vi.9 |

| Westward North Key | 188,000 | 142,500 | 51,300 | nine,500 | 31.ane | 5.7 | 184,400 | iii,600 | 1.nine |

| Minnesota* | 49,900 | 35,000 | 14,100 | 2,100 | 33.1 | 5.0 | 47,000 | two,900 | 5.9 |

| Iowa | 7,300 | 5,500 | 1,600 | 200 | 25.6 | 3.ix | 6,800 | 500 | half dozen.8 |

| Missouri | 19,800 | 12,300 | 1,900 | 200 | 11.ix | 1.3 | 14,000 | v,800 | 29.ii |

| N Dakota* | 25,900 | xx,200 | 8,500 | 1,600 | 36.eight | half-dozen.seven | 27,100 | -1,200 | -4.v |

| South Dakota* | l,600 | 45,000 | 17,800 | 4,100 | 37.2 | viii.5 | 58,700 | -8,100 | -sixteen.0 |

| Nebraska* | 12,400 | ix,200 | iii,600 | 800 | 33.6 | 7.1 | 12,100 | 300 | two.8 |

| Kansas | 22,000 | fifteen,400 | 3,800 | 500 | twenty.4 | 2.vii | 18,700 | iii,300 | fifteen.0 |

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Census." National Research Council. 1996. Irresolute Numbers, Irresolute Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/5355.

×

Suggested Commendation:"iv The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

| Census Counts | Average Annual Charge per unit a | Estimated 1990 Population | Error of Closure (Unsaid Migration) | ||||||

| Region, Sectionalization and State | 1990 | 1980 | Births 1980–1990 | Deaths 1980–1990 | Birth | Expiry | Amount | Percent b | |

| South Atlantic | 172,300 | 118,700 | 23,700 | 4,900 | 16.three | 3.3 | 137,600 | 34,700 | xx.one |

| Delaware | two,000 | 1,300 | 200 | 100 | xi.3 | four.five | 1,400 | 600 | 28.six |

| Maryland | 13,000 | 8,000 | 1,500 | 100 | 14.vii | 1.two | nine,400 | 3,500 | 27.ii |

| District of Columbia | 1,500 | 1,000 | 100 | 0 | 5.2 | ii.6 | 1,100 | 400 | 27.5 |

| Virginia | fifteen,300 | nine,500 | ane,300 | 200 | 10.5 | 1.5 | 10,600 | 4,700 | 30.8 |

| W Virginia | 2,500 | 1,600 | 100 | 0 | 4.ix | 0.6 | one,700 | 800 | 31.0 |

| Northward Carolina* | lxxx,200 | 64,700 | 16,000 | iii,900 | 22.one | five.3 | 76,800 | iii,400 | iv.2 |

| S Carolina | viii,200 | 5,800 | 800 | 100 | 12.1 | ane.3 | 6,500 | i,700 | 21.0 |

| Georgia | xiii,300 | 7,600 | 900 | 100 | nine.0 | 0.8 | viii,500 | 4,900 | 36.5 |

| Florida | 36,300 | 19,300 | 2,800 | 400 | 10.0 | i.5 | 21,600 | fourteen,700 | xl.five |

| East South Central | 40,800 | 22,500 | three,500 | 700 | eleven.0 | 2.1 | 25,300 | xv,500 | 38.0 |

| Kentucky | 5,800 | 3,600 | 400 | 0 | nine.1 | 1.0 | 4,000 | 1,800 | 30.9 |

| Tennessee | 10,000 | 5,100 | 600 | 100 | viii.5 | 0.8 | 5,700 | iv,400 | 43.4 |

| Alabama | 16,500 | 7,600 | 600 | 100 | iv.8 | 0.7 | 8,100 | 8,400 | 51.1 |

| Mississippi | 8,500 | 6,200 | 1,800 | 500 | 25.1 | vi.5 | 7,600 | 1,000 | xi.iv |

| Westward South Central | 349,600 | 231,000 | 62,900 | x,800 | 21.7 | 3.7 | 283,100 | 66,500 | nineteen.0 |

| Arkansas | 12,800 | 9,400 | 1,500 | 100 | thirteen.nine | 1.3 | 10,800 | ane,900 | xv.2 |

| Louisiana | xviii,500 | 12,100 | 2,900 | 300 | 19.one | 1.9 | fourteen,700 | 3,900 | 20.8 |

| Oklahoma* | 252,400 | 169,500 | 52,600 | 9,900 | 24.9 | 4.vii | 212,200 | 40,200 | xv.9 |

| Texas | 65,900 | 40,100 | 5,800 | 500 | 10.9 | 0.nine | 45,400 | 20,500 | 31.1 |

| Mountain | 480,500 | 364,400 | 135,200 | 23,600 | 32.0 | 5.6 | 476,000 | 4,500 | 0.ix |

| Montana* | 47,700 | 37,300 | fifteen,000 | 3,100 | 35.3 | 7.2 | 49,200 | -1,500 | -3.1 |

| Idaho* | thirteen,800 | 10,500 | 3,200 | 700 | 26.five | 5.9 | xiii,000 | 800 | v.v |

| Wyoming* | 9,500 | 7,100 | 3,100 | 600 | 37.8 | 6.7 | 9,700 | -200 | -2.0 |

| Colorado | 27,800 | xviii,100 | v,700 | 600 | 25.0 | 2.six | 23,200 | 4,600 | 16.5 |

| New United mexican states* | 134,400 | 106,100 | 37,600 | 6,500 | 31.2 | v.iv | 137,200 | -2,800 | -2.ane |

| Arizona* | 203,500 | 152,700 | 58,600 | 10,300 | 32.9 | 5.8 | 201,100 | 2,500 | 1.two |

| Utah* | 24,300 | 19,300 | 6,900 | 800 | 31.viii | 3.nine | 25,300 | -one,100 | -4.3 |

| Nevada* | xix,600 | 13,300 | 5,000 | 1,000 | thirty.half-dozen | half-dozen.0 | 17,400 | 2,300 | xi.6 |

| Pacific | 452,900 | 356,400 | 105,900 | 15,400 | 26.two | 3.8 | 446,900 | half-dozen,100 | i.iii |

| Washington* | 81,500 | 60,800 | 18,500 | 3,500 | 26.0 | iv.9 | 75,800 | 5,700 | vii.0 |

| Oregon* | 38,500 | 27,300 | seven,100 | 1,200 | 21.half dozen | three.7 | 33,200 | 5,300 | 13.eight |

| California | 242,200 | 201,400 | 52,400 | 5,400 | 23.6 | ii.5 | 248,400 | -6,200 | -2.6 |

| Alaska* | 85,700 | 64,100 | 26,300 | five,100 | 35.1 | 6.8 | 85,300 | 400 | 0.4 |

| Hawaii | five,100 | two,800 | one,600 | 100 | 40.6 | 3.3 | 4,200 | 900 | 16.9 |

| Note: All figures include Eskimos and Aleuts. Births projected for 1989–1990; deaths for 1988–1990. * Indian states include all states with 3,000+ Indians in the 1950 census, except California. a Rates per one,000 mid-menses population. b Base of operations of percentage is estimated 1990 population. | |||||||||

Suggested Commendation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Quango. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Council. 1996. Irresolute Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

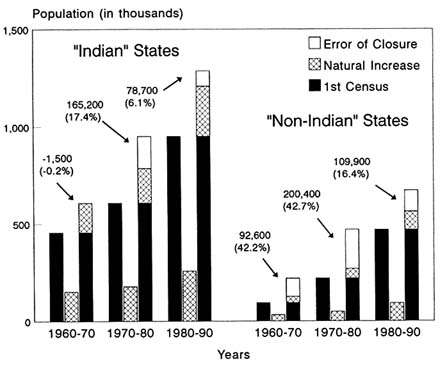

FIGURE iv-2 Error of closure past decade and state groups for American Indians, 1960–1990.

and are designated "not-Indian states." For each group of states, we can define fault of closure equally above. The measure is and so large for many states that it must be interpreted every bit indicating changes in self-identification.

For the 1960–1970 decade, the "Indian" states had essentially no mistake of closure—actually a negative mistake of closure amounting to 1,500 persons, or 0.2 percent of the population (Figure four-ii). This magnitude indicates footling change in reporting or possibly a small-scale amount of out-migration from the "Indian" states. The remaining 32 "non-Indian" states, however, showed a growth exceeding natural increase (i.e., error of closure) of 93,000, or 42 percent of the 1970 population of these states. Thus, the big increment from changing self-identification in 1970 was completely confined to the states that historically had non had significant American Indian populations.

Like patterns occurred in the next two decades, although not to the extreme shown in the 1960–1970 decade. For 1970–1980, the "Indian"

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Census." National Inquiry Council. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/5355.

×

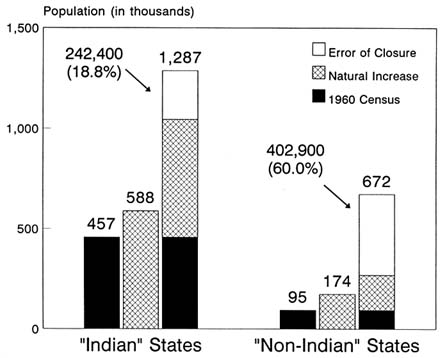

FIGURE 4-3 Error of closure past state groups for American Indians, 1960–1990.

states had an fault of closure of 165,000 or 17 per centum, whereas in the "non-Indian" states it amounted to 200,000, or fully 43 pct of the 1980 population in these states. The errors were more muted for 1980–1990:79,000 or half dozen percent in the "Indian" states and 110,000 or 16 percent in the "non-Indian" states. (Come across Table iv-5 for full detail on the 1980–1990 errors of closure.) Thus, the pct errors for each decade are all smaller in the "Indian" states than for every decade in the ''not-Indian" states. For the entire xxx-year period, the error of closure in the "Indian" states is 242,000 or 19 percentage of the 1990 population, whereas it is 403,000 or sixty percentage in the "non-Indian" states (Effigy 4-3). These patterns imply that shifts in identification are more than likely to occur in areas without big concentrations of American Indians or meaning reservation populations. In the "Indian" areas, which accept reservations and big concentrations, identification as American Indian is more than established by both self and customs and then is less likely to change over time.

Suggested Citation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Quango. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Census and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Printing. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

Births and Deaths

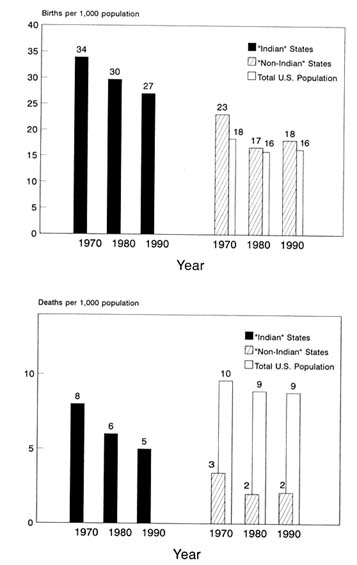

Crude nascence and expiry rates demonstrate further the incompatibility of demography and vital statistics data on American Indians. Directly ascertainment of substantial inconsistencies in race reporting on matched birth and infant death certificates has been reported (Hahn et al., 1992). The rough rates also show inconsistencies and changes in racial identification of American Indians over time. Rough nativity (and death) rates are measured as births (deaths) divided by population. The birth (decease) data are collected by NCHS using its own data drove method and classification for racial identification. To the extent that changes in cocky-identification are captured in the census and not in vital statistics, birth and death rates will exist excessively low in areas where there is a great deal of over reporting as American Indian in the census. In other words, the demography figures volition be inflated relative to the vital statistics in those areas.

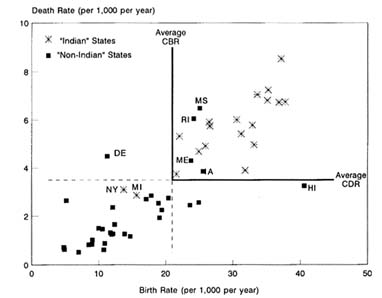

Figure 4-4 shows the differences in rough nascency and expiry rates between "Indian" and "non-Indian" states for 1970, 1980, and 1990. Birth rates in "Indian" states are substantially higher than in the remaining ''not-Indian" states, which have American Indian nativity rates approximating (but slightly college than) the rates for the total population. This pattern does not, past itself, prove that there are data inconsistencies. Birth rates in the "non-Indian" states may simply exist lower than the rates in the "Indian" states. However, taken together with the patterns of crude death rates, the birth rates do support the data inconsistency hypothesis.

The patterns of crude death rates are much more farthermost and striking than those of the birth rates. In fact, the death rates are non consistent with simple demographic differences across united states of america. The death rates in "Indian" states are higher—a groovy deal higher—than those for American Indians in the "not-Indian" states. In fact, the decease rates in "non-Indian" states are and then low that they suggest serious under identification in the vital statistics (numerator) or over reporting as American Indian in the census data (denominator). The patterns across time and across the groups of states provide another strong indication of increasing identification every bit American Indian in the "non-Indian" states, as well as substantial differences in identification between the census and vital statistics systems.

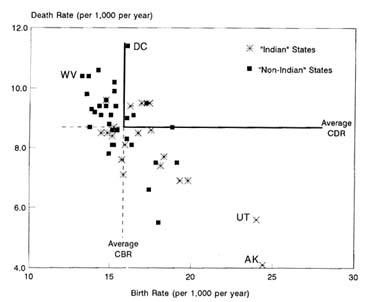

The potent influence of the denominator (i.eastward., the census count) in the vital rates tin can exist demonstrated in another fashion. In the United States, loftier crude nascency rates in states are normally associated with low crude death rates and vice versa, because of age-structure effects. In other words, the high rough birth rates usually lead to a relatively immature population with large concentrations of children and adults of child-bearing age, i.eastward., low-death-rate age groups. Such historic period structures tend to accept low

Suggested Citation:"four The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Research Council. 1996. Irresolute Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

FIGURE 4-iv Rough birth and death rates by country groups for American Indians, 1970–1990.

crude expiry rates. Conversely, states with high crude death rates tend to have high percentages of elderly persons and thus low crude birth rates. Utah (rough birth rate of 24.0 per thousand total population and rough expiry rate of 5.6 in the 1980s) and Florida (crude birth rate of fourteen.ii and crude death rate of 10.six) provide extreme examples of this negative relationship.

Suggested Citation:"iv The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Beyond Demography." National Inquiry Council. 1996. Irresolute Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Census and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5355.

×

Overall, the negative human relationship between rough nativity rates and rough expiry rates for the total population at the land level is very strong, with a correlation coefficient of -0.73 for the 1980s.

The American Indian population by state, however, shows just the opposite—a strong direct relationship between American Indian birth and expiry rates in the 1980s (shown in Table 4-5). The correlation coefficient between the two is extraordinarily high at +0.85. The "Indian" states have high American Indian birth and death rates, whereas the other states are low on both. (Encounter Figure iv-5 and 4-6 for the strongly contrasting patterns in the relationship between crude nascency rates and rough death rates for the total population and American Indians.) This pattern, so contrary to demographic expectations, must be driven past the size of the denominator (i.e., the census count), rather than the historic period structure and demographic behavior of the population. The very large denominators in "non-Indian" states artificially lower the computed crude birth rates and crude decease rates because of the key inconsistency between census data and vital statistics.

Determination

In general, the 1990 demography data on American Indians announced to capture the basic demographic features of this population, such every bit the historic period structure and size, merely shifts in self-identification suggest some circumspection in analyses of this population. The 1990 census data are somewhat more than consistent with vital statistics and the previous census than in other decades, but some inconsistencies notwithstanding remain. Although there were some changes in self-identification equally American Indian over the 1980–1990 decade, the shifts were smaller, both absolutely and proportionately, than in the previous two decades. Even with these smaller shifts, however, individuals identifying as American Indian were much more probable to be associated with organized American Indian groups (eastward.g., tribes, recognized bands, Alaska Native villages) in some areas (due east.thou., "Indian" states) than in others. Similarly, community recognition of individuals equally American Indian was more than probable to agree with the individual's response to the demography in these same areas.

In sum, the dissimilar patterns of population growth and change in "Indian" and "non-Indian" states imply a need for some caution in interpreting census data, only do not rule out the utility of the data for assessing the social, demographic, and economic situation of the American Indian population. Recognized inconsistencies betwixt 1990 census data on American Indians, on the ane hand, and vital statistics or the previous census, on the other, point to the desirability of restricting some analyses to certain areas and groups or proceeding with care and conducting specific

Suggested Citation:"iv The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Demography." National Research Quango. 1996. Changing Numbers, Irresolute Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Wellness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: x.17226/5355.

×

FIGURE 4-five Birth and death rates past country for American Indians, 1980–1990. Annotation: Populations based on demography counts.

Effigy 4-6 Nascency and decease rates by land for total population, 1980–1990.

Suggested Commendation:"4 The Growing American Indian Population, 1960-1990: Across Demography." National Inquiry Quango. 1996. Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: ten.17226/5355.

×

analyses to address information compatibility issues. However, for the areas with the largest concentrations of American Indians, the data should be extremely useful for analyzing socioeconomic and demographic conditions of dissimilar American Indian populations and other racial groups.

References

Eschbach, K. 1993 Changing identification among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Demography 30(4, November):635–652.

Fix, M., and J.S. Passel 1994 Clearing and Immigrants: Setting the Record Straight. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute.

Hahn, R. A., J. Mulinare, and Southward. M. Teutsch 1992 Inconsistencies in coding of race and ethnicity between nativity and decease in U.Southward. infants . Journal of the American Medical Association 267:259–263.

Harris, D. 1994 The 1990 Census count of American Indians: What do the numbers really mean? Social Science Quarterly 75 (September):580–593.

Passel, J. Due south. 1976 Provisional evaluation of the 1970 Census count of American Indians. Demography 13:397–409.

Passel, J. S. 1992 The growing American Indian population, 1960–1990. Unpublished paper presented at the almanac meetings of the American Statistical Association, Boston, MA, Baronial.

Passel, J. S., and P. A. Berman 1986 Quality of 1980 Census data for American Indians. Social Biological science 33:163–182.

Robinson, J. G., B. Ahmed, P. Das Gupta, and K. A. Woodrow 1992 Interpretation of Coverage in the 1990 United States Census Based on Demographic Analysis. Unpublished paper of the Population Sectionalization, U.S. Bureau of the Demography, Washington, D.C.

Snipp, C. Thousand. 1989 American Indians: The First of This Land. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Waters, M. C. 1990 Ethnic Options. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Population Increases That Resulted From the Baby Boom of the 1950s and 1960s Contributed to a

Source: https://www.nap.edu/read/5355/chapter/7

0 Response to "Population Increases That Resulted From the Baby Boom of the 1950s and 1960s Contributed to a"

Post a Comment